Slipstream – Jenn E Norton

Judith & Norman Alix Art Gallery, October 4, 2019 – January 5, 2020

Loïe Fuller. Not many people know this name today. It was a surprise to find Loïe Fuller mentioned in the introduction to the exhibition Slipstream as a focus of the work. Once, Fuller was revered as an innovator; now she is an almost obscure figure. Years ago, I watched an early 20th century short film of Fuller dancing on a French stage. The images of her movements were so different and unexpected; they stayed with me for a long time. That film is on YouTube now, along with a number of others paying homage to her achievements. Over a century ago, Fuller and others, such as Isadora Duncan, took the lead in the development of modern dance. In the last few years there has been a resurgence of interest in her achievements.

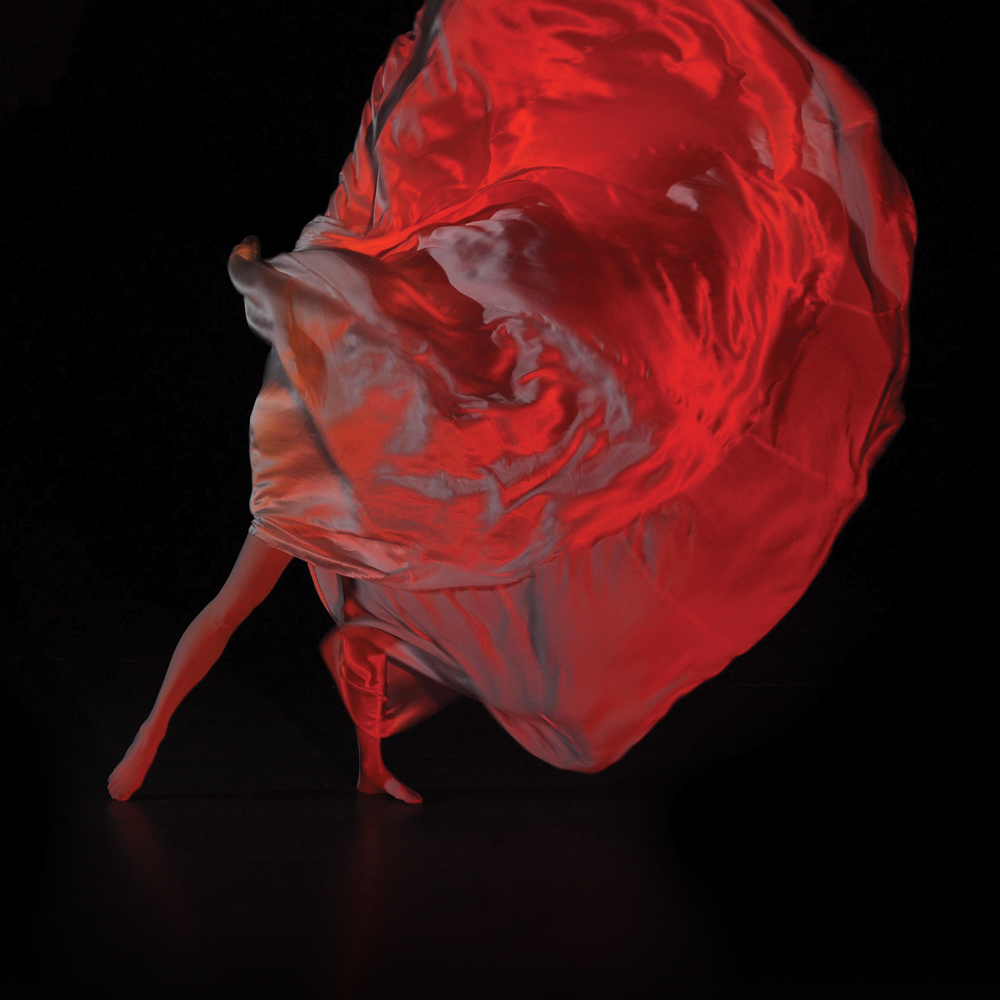

Fuller’s innovative dance was focused not on the body, but on the voluminous silk dress she manipulated with her movements, including broad sweeping strokes of her arms that seemed to be extended beyond their normal length. It was mesmerizing and sensuous. American audiences were not too responsive (Fuller was originally from Illinois), but French audiences reacted with amazement. Fuller’s new approach to dance and her use of new colour projection techniques that she developed and patented were advanced and startling in her own day.

Given my memories of that early film, I was interested to see how Norton would treat Fuller’s innovations. I discovered that Slipstream is Norton’s reconstruction of Fuller’s ideas using 21st century modes and technologies that would no doubt have appealed to the dancer. This is a physically engaging art experience. Entering a darkened gallery, you face a circle of six large monitors. You step inside the circle in order to watch the action happening on the screens that are placed at eye level.

Two of us happened to arrive at a moment when the screens were all blank and there was no sound. As we moved into the circle, a figure appeared on one screen, moving through a darkened space in ways that created waves of the white silk of her dress. At times she was caught in a spotlight that followed her as she moved from left to right. The timing was such that there was a slight gap in the action before she reappeared on the next screen, as though she was in the room with us. The spotlight changed from brilliant white to bright red, blue, and other vivid colours.

Two of us happened to arrive at a moment when the screens were all blank and there was no sound. As we moved into the circle, a figure appeared on one screen, moving through a darkened space in ways that created waves of the white silk of her dress. At times she was caught in a spotlight that followed her as she moved from left to right. The timing was such that there was a slight gap in the action before she reappeared on the next screen, as though she was in the room with us. The spotlight changed from brilliant white to bright red, blue, and other vivid colours.

It was a bit unnerving, because we were turning in the enclosed space to follow the dancer. We went around and around as she did. There were pauses in the action and we waited to see where she would next appear, looking over our shoulders, turning in response to her next appearance.

We were at once audience intensely watching the performance and part performers on the stage with the dancer, especially since we were reflected on the screens. It is interesting that it was only gradually that we took note of our reflections, so that I was finally drawn to closely examine a monitor and commented on its silvered surface.

Adding to this physically jarring experience was the sound – not music, but a swishing noise that at times grew so loud it was like the roar of an ocean wave. The figure sometimes appeared close to the screen, partly cut off by the frames but still intimidating. At other times we heard the whooshing sound and searched the screens for her, finally seeing her emerge from the dark in the distance. We never actually saw the dancer’s face, which was always darkened.

We turned and turned in our space, following the dancer in hers, and then there appeared on the screens what seemed to be mercury-like tracings of the arcs of her movements. These slivery notations hang there on the surface, translating the dancer’s moves into another element, suggesting a different level of reality, emphasizing the sculptural quality of the movement.

Had we been performers in the dance? What would it be like to see this with a larger group of people, everyone turning, following the dancer, and seeing themselves in the highly reflective screens? The mirroring quality of the screens includes us in the work: our turns, shifts, gestures, gazes, combining with the faceless dancer’s acts.

Norton has created a work that is embedded in my memory. I had not thought about Loïe Fuller in such a long time and my mental image of her dance was vague. Now I keep reliving the vision of this contemporary dancer, affected by such intense physicality: sight, thought, reflection, being intermeshed with movement. Slipstream demands that kind of response. At the same time, Norton brings the ideas of Loïe Fuller to life again.

Centred.ca

By Madeline Lennon, Professor Emerita

Visual Arts, Western University

October 30, 2019

Original Article